What Is Telemedicine and Telehealth?

What Is Telehealth?

Telehealth is the use of electronic data and long-distance communication technologies for healthcare and health-related services. Examples include visits performed using videoconferencing devices, store-and-forward imaging, and text messages that provide patient education.

What Is Telemedicine?

Telemedicine is a subset of telehealth, specifically focused on remote clinical services. In a remote service, the healthcare provider is not physically present with the patient. It may help to recall that “tele-” means at a distance.

Does Everyone Use the Same Definitions of Telehealth and Telemedicine?

The definitions above are only a starting point because organizations often have their own ways of explaining the difference between telehealth and telemedicine. Those who perform telehealth and telemedicine services and claim reimbursement for them need to be aware of the variations in definitions to ensure compliance with the various rules surrounding this area of healthcare.

A Brief History of Telehealth and Telemedicine

Telehealth and telemedicine today owe their start to the first times telephones and radios were used for health purposes. According to a World Healthcare Organization (WHO) report, which uses the terms telehealth and telemedicine interchangeably, telemedicine dates to the mid to late 1800s. But early services weren’t limited to patients getting advice from doctors on the phone. As early as 1906, a journal article reported electrocardiographic data being transmitted over telephone wires the previous year by a Dutch physician.

In the United States, transmission of radiographic images started in the 1950s, and an example of telehealth videoconferencing occurred in 1959, with the Nebraska Psychiatric Institute using the technology to provide therapy to patients and to train medical students at a Nebraska state hospital. In the 1960s, telemedicine advances occurred as military and space technology groups explored the capabilities of remote services.

The relatively recent rise of internet-connected devices and web-based applications has driven a growth in telehealth and telemedicine use and its possibilities. For instance, many patients and practitioners now have easy access to email, video calls, and cameras that produce digital images. There are also patient-facing health portals, which are secure websites that allow patients to access their personal health information and, in some cases, interact with healthcare providers. All of these developments help expand the number of people who can benefit from telehealth and telemedicine, and add to the types of potential communications.

What Are the Types of Telehealth?

The Center for Connected Health Policy (CCHP) lists four telehealth modalities, described below. CCHP’s National Telehealth Policy Resource Center project is funded by a grant from the U.S. Department of Health and Human Services (HHS), and the organization works with the 12 regional telehealth policy resource centers (TRCs) nationwide. Together they make up the National Consortium of Telehealth Resource Centers (NCTRC), which helps healthcare organizations operate telehealth programs for medically underserved communities. So, while these types of telehealth aren’t the only ones you may see referenced, these categories are used by many stakeholders across the U.S.

4 Types of Telehealth:

Live video telehealth is an audiovisual interaction between a provider and another individual (patient, caregiver, or provider). The telecommunications system used allows for a real-time remote encounter in place of an in-person visit. This is an example of synchronous telehealth, meaning it happens at the same time rather than the provider evaluating transmitted data later.

Mobile health, or mHealth, is the use of mobile devices, often through application software (apps), to provide information and services to patients. Text messages that encourage healthy behavior are an example.

Remote patient monitoring is the collection of health data, such as blood sugar or heart rate, from a patient and digital transmission of the information to healthcare providers in another location for assessment. Also called RPM, this form of telehealth may have benefits like reducing hospitalizations and improving quality of life for the patient.

Store-and-forward telehealth is also called asynchronous because it is not a real-time method. Recorded health information is transmitted to a practitioner for evaluation or another service. For instance, a radiologist may receive an X-ray through a secure system to provide an interpretation.

What Are Telecare and Connected Health?

Telehealth and telemedicine aren’t the only terms used for areas that merge telecommunications technology and healthcare. Telecare and connected health are among the many other possibilities. As with telehealth and telemedicine, the definitions for these terms can vary widely, including by country, but the definitions below offer some insight into how the terms are used.

Telecare is the use of technology that helps people stay independent in their own homes, such as fitness apps, digital medication reminders, and tools that connect individuals with their caregivers, according to the Federal Communications Commission (FCC).

Connected health is an all-encompassing term for telecare, telehealth, telemedicine, mobile health, and similar concepts that bring together health and telecommunications. Technology enabled care (TEC) is another term for connected health.

Medicare and Telehealth

Third-party payer coverage and reimbursement of telehealth and telemedicine influence whether healthcare providers offer the services and whether patients choose to participate. Medicare’s rules regarding telehealth services are a good place to start for understanding the relationship between insurers and telehealth services because there are tens of millions of Medicare beneficiaries across the U.S.

Note: The information below covers Medicare’s typical rules for telehealth. For information about significant changes to Medicare telehealth rules in place during the public health emergency (PHE) due to COVID-19, see AAPC Knowledge Center’s COVID-19 page and check Medicare resources for the guidance that applies to your date of service.

How Does Medicare Define Telehealth?

A “Medicare telehealth service” is a service that a provider normally furnishes in person but instead furnishes using real-time, interactive communication technology, according to the 2019 Medicare Physician Fee Schedule (MPFS) final rule. The service must comply with Section 1834(m) of the Social Security Act (the Act), described later in this article.

The Act lists office visits and office psychiatry services as two examples of telehealth services, and Medicare has generally added similar services to its list of covered telehealth services. (Read more about that in the section “Medicare’s List of Telehealth Services” below.) “Certain other kinds of services that are furnished remotely using communications technology are not considered ‘Medicare telehealth services’ and are not subject to the restrictions articulated in Section 1834(m) of the Act,” the 2019 MPFS final rule states.

Not All Remote Services Are Medicare Telehealth Services

The important point to learn from Medicare’s definition of telehealth is that it differs from the typical use of the term. Services routinely furnished using communication technology are not telehealth services under Medicare rules.

For instance, suppose a physician provides a virtual check-in using an audio-only phone call or an audio-video interaction to see if a patient needs an office visit. Medicare does not consider the virtual check-in to be telehealth because it is not a service the provider normally performs in person. Similarly, the Medicare telehealth code list does not include the medical codes for electrocardiographic telemetry patient monitoring with remote surveillance.

As counterintuitive as Medicare’s definition of telehealth may seem, the end result is that Medicare has been able to cover remote services and pay them on the MPFS without making them subject to the strict geographic and other limitations that apply to “Medicare telehealth services” as described in Section 1834(m) of the Act.

What Does Social Security Act Section 1834(m) Say About Telehealth?

Knowledge of the technicalities in Section 1834(m) of the Social Security Act is essential to compliance with Medicare rules for telehealth, particularly the limitations on the originating site where the beneficiary is located.

Medicare Part B

Section 1834 is categorized under “Part B — Supplementary Medical Insurance Benefits for the Aged and Disabled” in Title XVIII of the Act. Medicare Part B covers things like doctor and other healthcare providers’ services and outpatient care, durable medical equipment, home health, and some preventive services.

Telehealth Providers

The HHS secretary will pay for telehealth services furnished by a physician or practitioner to an eligible Part B beneficiary.

A physician is a doctor of medicine or osteopathy, or a doctor of dental surgery or dental medicine

A practitioner is a physician assistant, nurse practitioner, or clinical nurse specialist; a certified registered nurse anesthetist; a certified nurse-midwife; a clinical social worker; a clinical psychologist; or a registered dietitian or nutrition professional

Providers cannot assume that they may perform and be paid for every Medicare telehealth service simply because their profession is included in the list. For instance, clinical psychologists and clinical social workers cannot bill or get paid for certain psychotherapy services, according to Medicare’s MLN booklet Telehealth Services. This booklet, also referred to as the Medicare telehealth services fact sheet, is a valuable resource telehealth providers should review in addition to Section 1834(m). (Medicare also posted a “Medicare Telemedicine Health Care Provider Fact Sheet” on March 17, 2020. That fact sheet is specific to COVID-19 PHE changes. For services performed during the PHE, be sure you’re using the latest guidance that applies to your date of service.)

Distant Site and Payment

The distant site is the location where the physician or practitioner providing the telehealth service is located. The distant site provider is paid the same as if the service had been furnished without a telecommunications system.

Originating Site and Payment

The originating site is where the patient receiving the telehealth service is located. A physician or practitioner does not have to be present with the patient at the originating site. The originating site gets a flat facility fee that may change each year. There is no payment to the originating site if it’s a home, which is possible in limited circumstances.

Section 1834(m) of the Act limits the originating site, where the patient is located, to one of these geographic areas in most cases:

An area designated as a rural Health Professional Shortage Area (HPSA)

The (HRSA) decides HPSAs, according to Medicare’s Telehealth Services booklet. There is a on the HRSA site to check if an address is eligible for Medicare originating site payment. Eligibility remains the same throughout the calendar year.

The (HRSA) decides MSAs, the Telehealth Services booklet states.

A county not included in a Metropolitan Statistical Area (MSA)

An entity that participates in a federal telemedicine demonstration project

The originating site itself must be one of these:

The office of a physician or practitioner

A Critical Access Hospital (CAH)

A Rural Health Clinic (RHC)

A Federally Qualified Health Center (FQHC)

A hospital

A hospital-based or CAH-based renal dialysis center (including satellites)

A skilled nursing facility (SNF)

A community mental health center

A renal dialysis facility for purposes described in Section

That section states that a patient with end stage renal disease (ESRD) getting dialysis at home may opt to have monthly ESRD-related clinical assessments using telehealth after the first three months of home dialysis. The patient must have a face-to-face clinical assessment without telehealth at least once every three consecutive months.

An individual’s home if the patient meets the ESRD criteria above or is receiving treatment for a substance use disorder or a co-occurring mental health disorder

The originating site geographic limitations (HRSA, outside of an MSA, or demonstration project) do not apply to the monthly ESRD-related visits and substance use treatment services mentioned in the bullet list above.

The Act also lists originating site exceptions for stroke treatment. Another term you may see for stroke is cerebrovascular accident (CVA).

For diagnosis, evaluation, or treatment of acute stroke symptoms, the telehealth originating site (where the patient is) may be any hospital, CAH, mobile stroke unit, or other site the HHS secretary determines is appropriate.

The sites that are specific to this stroke care exception should not expect a facility fee.

For more about Medicare’s payment methodology for originating sites, see “Telehealth Originating Site Billing and Payment” later in this article.

Telehealth Services

As mentioned above, the Act lists office visits and office psychiatry services as examples of telehealth services. The Act also requires the HHS secretary to create a process for revising the list of services and related medical codes authorized for payment. To learn about this list, read “Medicare’s List of Telehealth Services” below.

Telehealth Devices

The Act provides the following information regarding telecommunications systems for telehealth: “In the case of any Federal telemedicine demonstration program conducted in Alaska or Hawaii, the term ‘telecommunications system’ includes store-and-forward technologies that provide for the asynchronous transmission of health care information in single or multimedia formats.”

Store and forward for Medicare telehealth is “the asynchronous transmission of medical information to be reviewed at a later time by physician or practitioner at the distant site. A patient’s medical information may include, but not limited to, video clips, still images, x-rays, MRIs, EKGs and EEGs, laboratory results, audio clips, and text. The physician or practitioner at the distant site reviews the case without the patient being present. Store and forward substitutes for an interactive encounter with the patient present; the patient is not present in real-time,” according to Medicare Claims Processing Manual, Chapter 12, Section 190.4.

The Medicare Claims Processing Manual goes on to explain that “Asynchronous telecommunications system in single media format does not include telephone calls, images transmitted via facsimile machines and text messages without visualization of the patient (electronic mail). Photographs must be specific to the patients’ condition and adequate for rendering or confirming a diagnosis and or treatment plan. Dermatological photographs, e.g., a photograph of a skin lesion, may be considered to meet the requirement of a single media format under this instruction.”

For telehealth services that are not part of a demonstration program in Alaska or Hawaii, Medicare requires use of an interactive audio and video telecommunications system that allows real-time communication between the distant site provider and the beneficiary at the originating site. The Medicare Claims Processing Manual, Chapter 12, confirms this requirement in Section 190.4.

Medicare’s List of Telehealth Services

Which services does Medicare cover for telehealth, assuming the many other requirements are met? Medicare’s List of Telehealth Services site provides the HCPCS Level II and CPT® codes eligible for coverage.

HCPCS Level II is Level II of the Healthcare Common Procedure Coding System. CMS develops and posts HCPCS Level II codes, which includes medical codes for medical devices, supplies, and drugs, as well as procedures and services not found in CPT®, but non-CMS payers may accept these codes, as well.

CPT® is Current Procedural Terminology, a code set that represents medical services and procedures provided by physicians and other healthcare practitioners. The American Medical Association (AMA) holds copyright in CPT®.

Technically, the CPT® code set is HCPCS Level I, but medical coders typically use “HCPCS” to refer to HCPCS Level II and use the term “CPT®” when discussing CPT® coding. However, Medicare and others may use “HCPCS” for both CPT® and HCPCS Level II codes.

Below are some examples of telehealth services Medicare Part B patients can receive when requirements are met, based on the CMS list of telehealth codes at the time of this article’s publication. This list changes (it changed drastically during the COVID-19 PHE), so specific codes are not included below. Providers and coders should confirm whether the services they provide are included in the file. Also, Medicare’s list of telehealth services is distinct from the codes marked by AMA in the CPT® code set using the telemedicine icon. See “AMA CPT® Telemedicine Codes and Services” later in this article for more about AMA’s telemedicine code list.

AWV: Annual wellness visits (AWVs) can be conducted using telehealth.

Consultations: In 2010, Medicare stopped accepting consultation codes except for telehealth consultation G codes, which are described in Medicare Claims Processing Manual, Chapter 12, Section 190.3.1. The codes apply to emergency department and inpatient services. These codes are a sort of exception to Medicare’s rule that services routinely furnished using communication technology are not telehealth services.

ESRD: As explained above, Medicare has specific rules about providing remote services for ESRD patients. The Medicare telehealth code list includes several codes for these ESRD services.

E/M: Office and other outpatient evaluation and management (E/M) services are among the most common services providers furnish to patients, and Medicare’s telehealth codes list includes these codes.

Facility services: Both subsequent hospital care and subsequent nursing facility care are on the Medicare telehealth code list.

OUD care: Opioid use disorder (OUD) treatment that includes care management and coordination, psychotherapy, and counseling are on the telehealth list.

Patient care plan: Services like transition care management may involve telehealth work to help the patient transition from a facility to a home setting.

Patient training: Training services such as diabetes self-management sessions are included on Medicare’s telehealth list.

Psychiatry and psychotherapy: Several CPT® codes on Medicare’s telehealth list apply to mental health care services, such as a psychiatric diagnostic evaluation.

Medicare provides more information about the conditions, such as frequency limitations, for certain telehealth services in Medicare Claims Processing Manual, Chapter 12, Section 190.

Medicare Telehealth Coding, Billing, and Payment

As with typical Medicare Part B services, providers submit medical codes that represent their telehealth services on paper or electronic claim forms to request reimbursement.

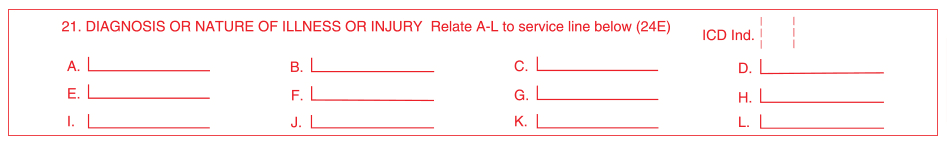

For physicians and other practitioners, CPT® and HCPCS codes identify the services and ICD-10-CM (International Classification of Diseases, 10th Revision, Clinical Modification) codes show the reason for the service, such as the patient’s diagnosis. Telehealth claims also may use medical code modifiers and place of service (POS) codes to provide more detail about the encounter.

Figure 1 shows some of the fields on the CMS-1500 claim form used by physicians and other practitioners (most use an electronic equivalent). For instance, the CPT® or HCPCS Level II code and relevant modifiers belong in field 24.D with the POS in field 24.B. Field 21 is for ICD-10-CM codes. Field 24.E (Diagnosis Pointer) shows which diagnosis from field 21 supports the CPT® or HCPCS Level II code in each row.

Figure 1. Sample from CMS-1500 claim form

Coding differs for telehealth distant sites and originating sites. The information below applies to Medicare’s standard telehealth reporting rules. For information about telehealth and telemedicine coding during the COVID-19 PHE, see AAPC Knowledge Center’s COVID-19 page or search Medicare’s website.

Telehealth Distant Site Billing and Payment

The distant site, where the furnishing provider is, submits claims to its Medicare Administrative Contractor (MAC), meaning the contractor that processes claims for the performing physician or practitioner’s service area. The MAC pays the correct amount based on the Medicare Physician Fee Schedule (MPFS) at the facility rate, rather than the non-facility (office) rate. The service has to be in the provider’s scope of practice per state law. The beneficiary is responsible for paying coinsurance and unmet deductible amounts, according to Medicare Claims Processing Manual, Chapter 12, Section 190.6.

The furnishing provider should use the applicable CPT® or HCPCS Level II code from Medicare’s list of telehealth codes. The appropriate POS for the distant site provider to report in CMS-1500 field 24.B (or the electronic equivalent) is 02 Telehealth. The physician or practitioner who uses POS 02 certifies that the patient receiving the service was at an eligible originating site. For ESRD-related services, use of POS 02 certifies that one visit per month met the face-to-face examination requirement, states Medicare Claims Processing Manual, Chapter 12, Section 190.6.1.

CAH: The rules differ slightly for Critical Access Hospitals (CAHs), which are participating Medicare hospitals that meet specific requirements, such as being in a rural area and having no more than 25 inpatient beds.

Distant site practitioners billing telehealth under CAH Optional Payment Method II use modifier GT Via interactive audio and video telecommunication systems on their institutional claims. In short, Payment Method II involves the CAH billing facility and professional outpatient services to the MAC when its physicians or practitioners reassign billing rights to the CAH.

“The payment is 80 percent of the Medicare PFS facility amount for the distant site service,” Medicare’s Telehealth Services booklet states.

Telehealth Originating Site Billing and Payment

The originating site, where the patient is, reports Q3014 Telehealth originating site facility fee to its MAC.

Medicare Claims Processing Manual, Chapter 12, Section 190.5, details the payment methodology for the originating site fee. According to the manual, the Medicare contractor pays the originating site facility fee as a separately billable Part B payment outside of other payment methodologies. For instance, a hospital outpatient department that is an originating site gets the Part B fee. It does not get payment based on Medicare’s Outpatient Prospective Payment System (OPPS).

The originating site receives the lesser of 80% of the actual charge or 80% of the originating site facility fee. CAHs are the exception, getting 80% of the originating site facility fee. The patient is responsible for coinsurance and any unmet deductible amount.

The manual provides additional details on things like bill types, making this an important resource for individuals responsible for claims. For example, the manual states that the type of service (TOS) for the telehealth originating site facility fee is “9,” which means “other medical items and services.” For A/B MAC (B) processed claims, POS 11 Office is the correct option for Q3014. POS codes are used on professional claims to indicate the entity where a service was rendered.

Stroke Care

For dates of service Jan. 1, 2019, and later, providers must use modifier G0 Telehealth services for diagnosis, evaluation, or treatment, of symptoms of an acute stroke to identify telehealth services for acute stroke symptoms in Medicare patients. The modifier is the letter G and the number 0. Distant sites using POS code 02 or CAHs should use the modifier. Telehealth originating sites that report Q3014 also should use modifier G0 to identify stroke care, according to Medicare Claims Processing Manual, Chapter 12, Section 190.3.7.

Asynchronous Telecommunications

The MLN telehealth booklet instructs providers that when they use asynchronous telecommunications systems, they must append modifier GQ Via asynchronous telecommunications system to the CPT® or HCPCS Level II code. Because Medicare typically requires real-time communication, use of this modifier certifies “the asynchronous medical file was collected and transmitted to you at the distant site from a Federal telemedicine demonstration project conducted in Alaska or Hawaii,” the booklet states.

AMA CPT® Telemedicine Codes and Services

Medicare’s list of telehealth services is distinct from the AMA’s list of “CPT® Codes That May Be Used For Synchronous Telemedicine Services,” which is located in Appendix P of the CPT® 2020 Professional Edition code book. Appendix P states that the codes are appropriate for reporting real-time telemedicine services that include interactive electronic telecommunications. The equipment must provide audio and video.

Appendix P also instructs you to indicate the use of telemedicine by appending modifier 95 Synchronous telemedicine service rendered via a real-time interactive audio and video telecommunications system to the code for the service. You may append modifier 95 only to those codes listed in Appendix P, according to “Telemedicine Services Modifier 95,” CPT® Assistant (October 2017). For added convenience in locating these codes, your CPT® code book or online coding resource may mark services from Appendix P using a star symbol in code listings.

Table 1 shows examples of services CPT® included in Appendix P in 2020. You may notice some overlap with Medicare’s list of telehealth services. Keep in mind that the list below does not include all the codes in Appendix P, and the codes CPT® allows for telemedicine services are subject to change each year.

2020 CPT® Codes for Telemedicine Services

Table 1: Examples of 2020 CPT® codes allowed for synchronous telemedicine services

Codes | Services |

|---|---|

90832-90838, 90845-90847 | Psychotherapy services and procedures |

90863 | Pharmacologic management |

90951, 90952, 90954, 90955, 90957, 90958, 90960, 90961 | End-stage renal disease services |

92227, 92228 | Remote imaging for retinal disease |

93228, 93229 | External mobile cardiovascular telemetry |

97802-97804 | Medical nutrition therapy |

99201-99205, 99212-99215 | Office/outpatient E/M |

99231-99233 | Subsequent hospital care |

99307-99310 | Subsequent nursing facility care |

99406-99409 | Smoking and tobacco use cessation counseling |

99495, 99496 | Transitional care management |

To ensure accurate coding and optimal reimbursement, healthcare organizations should research which procedure codes, modifiers, and place of service codes their payers allow for telehealth and telemedicine services. As you have already seen, Medicare and CPT® rules differ for reporting this type of healthcare, and other third-party payers may have their own policies.

Conclusion: Telehealth and Telemedicine Benefits and Challenges

As the use of telehealth and telemedicine continue to grow, providers, patients, payers, and policymakers all will be weighing the pros and cons of this evolving area.

Telehealth/Telemedicine in Rural Communities

An advantage for rural providers and patients is that telemedicine allows access to specialists not available in the local area. Patients may be more likely to seek care if they don’t have the expense and inconvenience of a trip. This quick access to care also can be lifesaving, as in the case of stroke acute-care patients.

Access to Care for Opioid Use Disorder and During COVID-19 PHE

The benefits of telemedicine are not limited to rural providers and patients. For instance, telemedicine also has played a role in addressing the opioid epidemic, offering patients options for getting help and support without always having to travel to a provider. And during the COVID-19 PHE many patients tried telemedicine for the first time, making them more comfortable with this approach to care. At least some of these patients are sure to want similar telemedicine visits in the future.

HIPAA and Telehealth/Telemedicine

Any change in how care is provided brings challenges, of course. As an example, healthcare organizations have to ensure they comply with Health Insurance Portability and Accountability Act (HIPAA) requirements to protect patient’s private health information when using telecommunications.

Costs of Telehealth/Telemedicine

Additionally, healthcare organizations must expect to spend time and money educating staff and patients on using telemedicine technology; evaluating, acquiring, and maintaining that technology; and keeping track of which services are covered by each payer and how that payer wants services reported.

Value-Based Care and Patient Care Outcomes

A final factor for telehealth and telemedicine is the shift to value-based care reimbursement models. These models emphasize patient outcomes rather than paying based solely on the number of services provided. Healthcare organizations are exploring how telemedicine and telehealth can improve both efficiency and results for patient care. While real-time telemedicine visits can reduce some care delivery costs, this isn’t the only avenue organizations should explore. For instance, sending electronic messages to patients may encourage compliance with treatment regimens, and remote monitoring of patients at home or in post-acute care may allow providers to catch and treat health concerns early. Both are examples of how broader telehealth use can result in cost savings, expand access to care, and create connections with patients so they are more likely to take the necessary steps to improve their health.

Last reviewed on June 11, 2022, by the AAPC Thought Leadership Team

About the author

Want to move up in your career?

Explore all the directions you can go with AAPC certifications.

Code faster, more confidently, and accurately — every time

When you code with Codify, you have an all-in-one resource at your fingertips to help you be the best coder you can be.

Telehealth: A New Era of Virtual Care Post Pandemic

In this workshop, explore the telehealth journey from pre-PHE to now. Understand evolving regulations, reimbursement, location restrictions, cross-state practice, HIPAA compliance, and OIG oversight.