Oncology & Hematology Coding Alert

ICD-10-CM Coding:

Factor This Knowledge Into Your Coagulation Disorder Coding

Published on Thu Dec 23, 2021

You’ve reached your limit of free articles. Already a subscriber? Log in.

Not a subscriber? Subscribe today to continue reading this article. Plus, you’ll get:

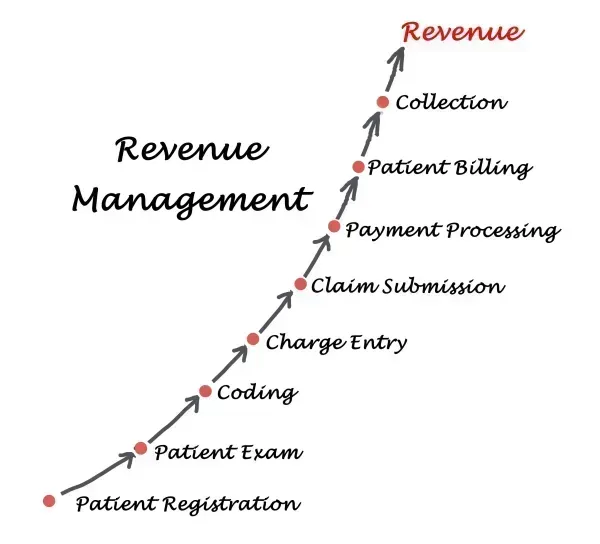

- Simple explanations of current healthcare regulations and payer programs

- Real-world reporting scenarios solved by our expert coders

- Industry news, such as MAC and RAC activities, the OIG Work Plan, and CERT reports

- Instant access to every article ever published in Revenue Cycle Insider

- 6 annual AAPC-approved CEUs

- The latest updates for CPT®, ICD-10-CM, HCPCS Level II, NCCI edits, modifiers, compliance, technology, practice management, and more

Related Articles

Other Articles in this issue of

Oncology & Hematology Coding Alert

- Screening and Testing:

Get the Answers to Your Frequently Asked PSA Testing Questions

Here’s how to understand the differences between these four prostate cancer tests. On the surface, [...] - Modifiers:

Unbundle Your Modifier 59 Understanding With These 2 Scenarios

Hint: Look to other modifiers and NCCI edit pair modifier indicators for correct application. You [...] - ICD-10-CM Coding:

Factor This Knowledge Into Your Coagulation Disorder Coding

What do 13 factors, hereditary conditions, and these Greek and Latin words have in common? [...] - You Be the Coder:

Elevate This Chronic Illness MDM Beyond Stable Status

Question: If a patient only has one chronic problem that is not worsening but is [...] - Reader Questions:

Include Biopsy in This Pleural Effusion Encounter

Question: Our provider drained pleural fluid and performed a needle pleural biopsy on a patient [...] - Reader Questions:

Take These Steps to Document Physicist Consults

Question: How do we document a special physics consultation with a radiation physicist? Michigan Subscriber [...] - Reader Questions:

Depend on This Definition to Determine Independent Historian’s Role

Question: Our provider recently performed an evaluation and management (E/M) service on an elderly woman [...]

View All