MDS Alert

Champion Your Pressure-Ulcer Coding With 6 Expert Tips

How to properly code worsening ulcers in M0800.

When the resident’s medical record or physician’s notes aren’t entirely clear, do you know how to determine whether an unidentified wound is in fact a pressure ulcer? Do you know when you must report a pressure ulcer as “worsening?” Follow this expert advice to get your Section M coding on-track.

1. Look to the Location for Clues

There are four different types of skin conditions that you must consider when coding Section M: pressure ulcers, diabetic foot ulcers, venous ulcers, and arterial ulcers. “When assessing an ulcer, one of the first and perhaps greatest clues as to the etiology is its location,” stressed Jennifer Pettis, RN, BS, WCC, consultant for the Centers for Medicare & Medicaid Services (CMS) Division of Nursing Homes, in a provider update presentation posted by CMS on March 20. (To view the presentation, go to www.youtube.com/watch?v=Ix6qoV0If0Y&feature=youtu.be.)

Example: Bony prominences, such as the sacrum, the coccyx, the heels and ischial tuberosities, are areas on the body that are known places where pressure ulcers develop, Pettis noted. A tuberosity is a rounded prominence, particularly a large prominence on a bone usually serving for the attachment of muscles or ligaments. You may also find pressure ulcers on skin subjected to excessive pressure, shear, or friction, as well as on bony deformities and skin beneath braces.

On the other hand, you’ll typically find diabetic foot ulcers on the plantar or bottom surface of the foot, closer to the metatarsal, Pettis said. And “venous wounds most commonly occur proximal to the medial or lateral malleolus or on the lower calf area of the leg.” The malleolus is the bony prominence on either side of the ankle, at the lower end of the fibula or tibula.

You can usually tell pressure ulcers apart from arterial ulcers pretty easily, because “arterial wounds do not typically occur over a bony prominence; they are usually seen on the tips and tops of the toes, tops of the feet, or distal to the medial malleolus or inner ankle,” Pettis added.

2. Watch for Exudate, Pain to Classify Ulcers

In addition to location, other clues that can help you to determine etiology include sensation, the amount of exudate, and the tissues in and surrounding the ulcer, stated Lori Grocholski, MSW, LCSW, with CMS’s Center for Clinical Standards and Quality, in the provider update video. Exudate is a material composed of serum, fibrin and white blood cells that escapes from blood vessels into a superficial lesion or area of inflammation.

Case in point: Although venous ulcers may or may not be painful, they are typically shallow with irregular wound edges and have a red granular or bumpy wound bed, Grocholski explained. Venous ulcers “tend to present with minimal to moderate amounts of yellow, fibrinous material and they generally have moderate to large amounts of exudate.”

“The surrounding tissues may be erythematous, or reddened, or appear brown-tinged due to a protein that contains iron called hemosiderin,” Grocholski said. “Leg edema or swelling may also be present.

Unlike venous ulcers, arterial ulcers are usually painful and have a pink wound bed or present with necrotic tissue. They have a deep, round punched-out appearance with irregular but distinct boundaries, and poor granulation tissue, Grocholski noted. Arterial ulcers typically have minimal or no bleeding and exudate. Other symptoms include coolness to the touch, absent pedal pulses, decreased pain when feet are dependent, increased pain and blanching when feet are elevated, delayed capillary refill time, hair loss at the top of the foot and toes, and toenail thickening.

Diabetic foot ulcers are usually deep with necrotic tissue, and have moderate amounts of exudate and callous wound edges, Grocholski illustrated. “The wounds are very regular in shape and the wound edges are even with a punched-out appearance.” These are not typically painful.

Pitfall: Although diabetic neuropathic ulcers usually occur on the foot’s plantar surface, a resident may develop foot deformities like Charcot Foot, Grocholski cautioned. “Charcot Foot occurs in people with significant neuropathy,” which causes weakening of the foot bones that may lead to fractures. These fractures may cause the foot to take on an abnormal shape, “often presenting with a ‘rocker bottom’ appearance,” she added.

3. Refer to Pressure Ulcer Definition for Etiology

When you’re attempting to identify a wound as a pressure ulcer, look at the definition first, Grocholski advised. The definition of a pressure ulcer, found on page M-4 of the RAI Manual, is: “A pressure ulcer is localized injury to the skin and/or underlying tissue usually over a bony prominence, as a result of pressure, or pressure in combination with shear and/or friction.”

Look out: You need to be aware of “really anything that could cause pressure to bony prominences or contribute to shearing of the skin,” Grocholski noted. But remember that “the appearance of skin surrounding the ulcer and characteristics of the drainage can vary greatly with pressure ulcers, regardless of the stage.”

4. Use These Guidelines for Proper Staging

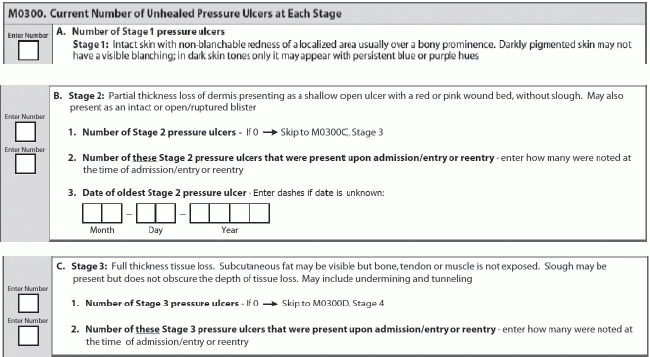

After you’ve determined that the lesion and/or skin condition is primarily related to pressure and you’ve ruled out other conditions, you need to code the pressure ulcer in M0300 — Current Number of Unhealed Pressure Ulcers at Each Stage. Grocholski offers the following tips for correctly staging pressure ulcers for Stages 1 through 4:

- Stage 1: (Report in M0300A — Number of Stage 1 pressure ulcers.) An observable, pressure-related alteration of intact skin, which may include changes in one or more of the following parameters:

o Skin temperature — area may be warmer or cooler than the surrounding tissue;

o Tissue consistency — area may be firmer or boggier than the surrounding tissue or opposite area;

o Sensation — pain or itching; and/or

o Pigmentation — area may be defined with persistent redness (in lighter pigmented skin), or with persistent red, blue or purple hues (in darker skin tones).

- Stage 2: (Report in M0300B — Stage 2 pressure ulcers.) Have partial thickness loss of dermis presenting as a shallow, open ulcer with a red-pink wound bed without slough.

- Stage 3: (Report in M0300C — Stage 3 pressure ulcers.) Full-thickness wound in which subcutaneous fat may be visible and which may include undermining or tunneling. Undermining is tissue destruction underlying intact skin along wound margins, while tunneling is empty space that can extend in any direction from the wound. Slough may be present but should not obscure the depth of tissue loss.

- Stage 4: (Report in M0300D — Stage 4 pressure ulcers.) Also a full-thickness wound with possible subcutaneous fat visible and undermining or tunneling. Bone, tendon, or muscle is exposed — visible or directly palpable. Slough or eschar may be present on some parts of the wound bed.

5. Pinpoint Whether Ulcer is Present on Admission

“In order for a pressure ulcer to be considered present on admission, it must be present at the time of admission, entry, or reentry,” Pettis said. The pressure ulcer must not be “acquired while the resident was in the care of the nursing home.”

What to do: “First consider current and historical levels of tissue involvement,” Pettis instructed. “And refer to scenarios that are detailed in the RAI User’s Manual for clarification.”

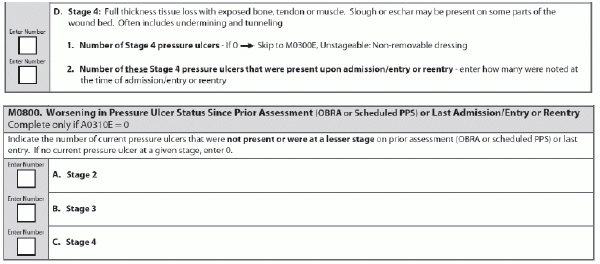

6. Pay Attention to ‘Worsening’ Language for M0800 Coding

In the latest RAI Manual update, CMS added language to item M0800 — Worsening in Pressure Ulcer Status Since Prior Assessment (OBRA or scheduled PPS) or Last Admission/Entry or Reentry. “CMS’s definition of worsening is, a pressure ulcer that has progressed to a deeper level of tissue damage and is therefore staged at a higher number using a numerical scale, one through four,” Pettis explained.

Problem: You can determine worsening in item M0800 only when you have numerical stages available for comparison, Pettis noted. For example, when a Stage 2 pressure ulcer becomes covered with slough, it has indeed clinically worsened to at least a Stage 3 pressure ulcer because Stage 2 ulcers cannot contain slough. But this distinction is not reflected in the Section M coding.

The information that CMS added to M0800 includes two important points:

1. If a pressure ulcer was numerically staged and becomes unstageable due to slough or eschar, you should not consider this pressure ulcer as worsened. “The only way to determine if this pressure ulcer has worsened is to remove enough slough or eschar that the wound bed becomes visible,” Pettis explained. “Once enough of the wound bed can be visualized and/or palpated such that the tissues can be identified and the wound can be restaged, the determination of worsening can be made.”

2. When two pressure ulcers merge, do not code the merged pressure ulcers as worsened, Pettis instructed. “Although two merged pressure ulcers might increase the overall surface area of the pressure ulcer, there would need to be an increase in numerical stage in order for it to be considered as worsened.”

MDS Alert

- Section M:

Champion Your Pressure-Ulcer Coding With 6 Expert Tips

How to properly code worsening ulcers in M0800. When the resident’s medical record or physician’s [...] - Section G:

Understand 'Rule Of 3' Steps Using 3 Scenarios

Remember to use sub-items when applying the third rule. Applying the Rule of 3 to [...] - ADLs:

How To Use The ADL Self-Performance Algorithm -- The Right Way

Tip: Keep definitions, Rule of 3 text handy while using algorithm. The October 2013 overhaul [...] - MDS 3.0:

Get Ready For MDS 3.0 & Dementia Care Survey Pilots

Dementia survey goes way beyond reducing antipsychotic use. The Centers for Medicare & Medicaid Services [...] - PEPPER:

Your PEPPER Is Now Available -- How To Access It

New: Comparison group includes all SNFs in the same state. Your Fourth Quarter fiscal year [...] - MDS 3.0:

Solve 3 Thorny MDS Questions

When you can — and can’t — report medications in J0100. What should you do [...] - Industry News to Use:

Could Functional-Status Quality Measures Be In Your Future?

Plus: SNF PPS proposed rule contains a wide array of policy, payment changes. The Centers [...]