Use the MDS for fall documentation, investigation, and care-planning.

Falls: The F-word no facility wants to utter, let alone deal with. Though the MDS is a functional assessment, you can use the information you record there to help anticipate the risk of a fall for a particular resident. If you’re thorough in your assessments, comprehensive in your recording, and creative in searching out patterns of behaviors or groupings of risk factors, the MDS canprove to be a significant tool in your fall-prevention arsenal.

First, think about the different sections of the MDS, says Jane Belt, Ms, Rn, RaC-Mt, QCP, Curriculum Development Specialist at American Association of Nurse Assessment Coordination (AANAC) in Denver, Colorado. You’re assessing behaviors and recording information on cognition, vision, hearing, mood, and balance, as well as medications, diseases, and special treatments. While dialysis or chemotherapy might have more immediate implications for your record keeping in Section O (Treatments, Procedures, and Programs), a resident who receives these treatments could be at a greater risk for falling, as well.

Use this kind of comprehensive, creative thinking to your advantage as an investigator, both as an individual and as a representative of your facility, Belt suggests. Prioritize accuracy in Section J, and remember that your Section J coding is trackable. “The MDS items on falls in Section J of the MDS must be accurate, and those results then are reported in the quality measures, which are easily tracked via the Five-Star rating system and the CASPER reports that are a part of each facility’s computer software.”

Start with Section J

To determine a resident’s risk for a fall, start with his or her history of falls during your first assessment. Falls are the leading cause of injury and death in older adults, so investigating a resident’s fall history and evaluating her risk for more falls is especially worth a facility’s due diligence to prevent further falls.

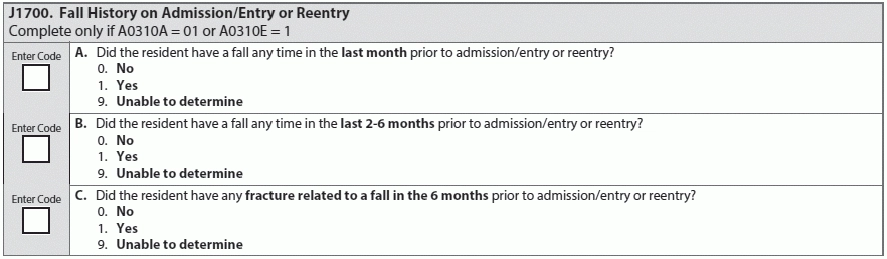

The lookback period for Item J1700 (Fall history on admission/entry or reentry) is six months from the resident’s entry date. If your answers for items A0310A (Federal OBRA Reason for Assessment, Admission) and A0310E (Is this Assessment the First Assessment?) are 01 or 1, respectively, make sure that the lookback date you’re using reflects the resident’s admission.

The RAI Manual’s tips for assessing J1700 (Fall history …) include a direct interview with the resident, as well as family or a significant other, about any history of any falls in the past month and in the past six months. Also review any interfacility transfer information, if available and applicable, as well as medical records from the past six months.

With this information at hand, and remembering that the lookback period is six months before entry/reentry, code J1700 (Fall history ....) A (… fall in the last month):

Use these same values (0, 1, 9) for J1700B (Falls in the last 2-6 months) and J1700C (Fracture related to fall in last six months).

Note: A fracture related to a fall is defined by the RAI Manual as “Any documented bone fracture (in a problem list from a medical record, an X-ray report, or by history of the resident or caregiver) that occurred as a direct result of a fall or was recognized and later attributed to the fall. Do not include fractures caused by trauma related to car crashes or pedestrian versus car accidents or impact of another person or object against the resident.”

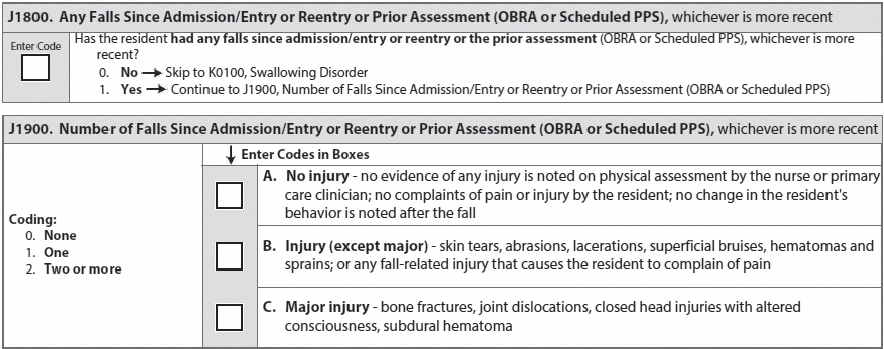

In evaluating item J1800 (Any falls since admission/entry or Reentry or Prior assessment [OBRA or Scheduled PPS]), you’re documenting any falls or intercepted falls since entry/reentry/prior assessment, whichever is most recent. Choose from 0 (No) or 1 (Yes).

For J1900 (Number of falls since admission/entry or Reentry or Prior assessment [OBRA or Scheduled PPS]), you’re coding the number of falls and the most severe of any fall-related injuries. Document each fall and every injury for the MDS. Your responses should reflect both the frequency and severity of your falls. Your values for each subsection (A, B, C) of J1900 (Number of Falls ….) are 0 (None), 1 (One), or 2 (Two or more).

The language of the MDS questions makes evaluation and recoding a little tricky in J1900. Basically, “If one fall occurred the coding would be ‘1’ in A, B, or C. If more than one fall occurred, you would code in A, B, or C the number that each injury or no injury occurred. The number in A, B, or C must equal the number of falls that occurred,” says Marilyn Mines, Rn, BC, RaC-Ct, Senior Manager at Marcum LLP, in Deerfield, Illinois.

For example: A team member’s notes indicate that Mrs. Dickens slipped/sagged out of her wheelchair while the team member was making her bed. The team member provides immediate assistance to get her back in her chair and right her, and is certain that there’s no evidence of injury. For J1900A (Number of falls ….), you would code 1 (One), because she fell but did not sustain any injuries.

“If one fall occurred the coding would be “1” in A, B, or C. If more than one fall occurred, you would code in A, B, or C the number that each injury or no injury occurred. The number in A, B, or C must equal the number of falls that occurred,” Mines says.

Another example: Mrs. Keats went to a baby shower for her great granddaughter, and upon her return, her daughter was very upset because she had slipped off of a toilet at the restaurant. Her daughter had been assisting her in the bathroom and caught her before she hit the floor. In this case, code 1 (One) for J1900A, because you’re documenting all falls, without injury, that occur while Mrs. Keats is a resident, even if any of the falls happen beyond the facility.

Example: Mr. Eliot suffered a stroke while waiting to be brought into the dining room and slipped onto the floor, hard. A CT scan reveals a subdural hematoma in a region of the brain separate from the blood clot, suggesting that Mr. Eliot suffered an injury from the impact of falling, even though he fell because of the stroke. For J1900C, you would code 1, despite the complexity of his situation. Why? You’re recording that Mr. Eliot fell and that his injury is “major” per the MDS/RAI Manual. It doesn’t matter what the cause is.

Remember: If an injury secondary to a fall is identified after the ARD, you must modify the MDS.

Go Beyond History and Assess Risk

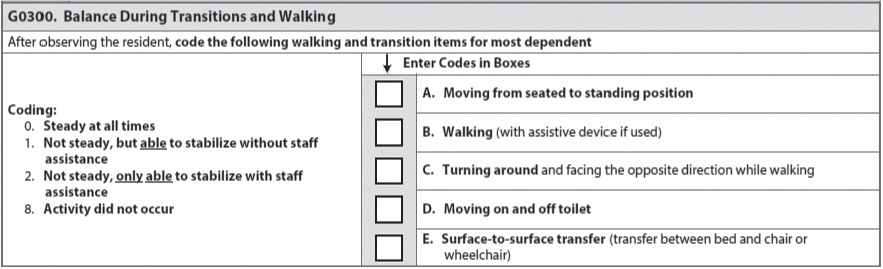

Section G (Functional Status) is a great place to start your MDS fall risk assessment. Items G0300A-G0300E (Balance During Transitions and Walking) have a 7-day lookback period. The best practice for completing this item is to have an interdisciplinary team observe and document mobility transitions (including transitions from stationary to ambulation and from sitting to standing) throughout the week. You can use their notesfrom those organic situations to make your assessment. However, you can conduct a more formal assessment if you do not have consistent documented information available.

“Trying to reduce falls in LTC is like being an investigator — you have to looks at all the cues — MDS, CAA, and any other information that might be gathered from the resident, staff, or family,” Belt says.

Physicality of Fall Risk

When assessing fall risk, look for issues with strength or steadiness that are noticeable in odd moments: For example, if the resident has trouble maintaining her balance while she’s sitting, even though she isn’t ambulating.

Other behaviors to look out for include:

In terms of evaluation, make sure you and team members are observing residents in their daily travels throughout your facility. Watch for signs and symptoms of pain or altered gait. Talk to your team members to make sure that they’re all involved in the observation of residents, and also to find out what they’ve seen or experienced.

Has a particular resident demonstrated a loss of balance or had difficulty transitioning, such as any unsteadiness during the act of sitting in a chair? Is she reaching for furniture or walls while moving around your facility? Sourcing this information can be informal — you’re investigating — but make sure you document what you find.

Look at Diagnoses and Medication

Diagnoses that affect body systems are important for assessing fall risk as well. Look for diagnoses affecting circulation and the heart; those that would affect or impede neuromuscular mobility or function; orthopedic diagnoses such as healing fractures; those impacting perception or sensation; and diagnoses that affect cognitive or psychiatric well-being.

In the MDS, you should look at Section C (Cognitive Patterns), Section E (Behavior), Section G (Functional Status), Section I (Active Diagnoses), and Section H (Bladder and Bowel) to assess risk. For example, both cognition and incontinence correlate with a higher fall risk, says Renee Kinder, Ms, CCC-sLP, RaC-Ct, Director of Clinical Education at Encore Rehabilitation Service in Louisville, Kentucky. For a full review of indicators of fall risk with a Care Area Assessment, look at the RAI Manual Appendix C.

Go further: The RAI Manual says you should complete a Care Area Assessment (CAA) if your completed MDS assessment suggests a need to further investigate a resident’s strengths, problems, and needs. “The fall CAA is triggered and must be completed when several areas of the MDS are coded a specific way. Information gleaned from this review identifies factors that can elevate risk,” Mines says. In other words, if your completion of the MDS assessment illustrates that a resident is at risk for falls, you need to complete the fall CAA — a formal, deeper investigation of how and why a resident is at risk.

Beware: Take special care in evaluating and observing any residents who are being treated with medication that can cause or increase lethargy or confusion. In the MDS, look at Section N (Medications) items such as antipsychotics (N0410A), anti-anxiety medications (N0410B), antidepressants (N0410C), and diuretics (N0410G). Don’t forget to check out the medication administration record for any cardiovascular medications, narcotics, or neuroleptics. “Falls risks significantly increase during the following three days after any medication change related to the central nervous system such as sedatives and anti-anxiety drugs,” Kinder says.

Consider the general wear of the human body, too. Older people’s vision is not as sharp, and the industry consensus is that seniors should have their vision evaluated at least once a year. If a resident wears glasses, find out how current her lens prescription is. If she is not currently wearing glasses, ask whether she used glasses in the past.

If your resident is especially mobile and functional, think about how her vision affects her perception during activities, especially activities that might involve increased risk of falls. “Single vision distance glasses may be considered for long distance walking or outdoor activities,” Kinder says.

Remember, too, that residents who have a history of falling are more scared of future falls, and that a fear of falling can become a risk factor in falling again.

Caution: Though it’s crucial to evaluate a resident’s likelihood of falling through information found in her own medical record, team member observations, and assessment, don’t forget to look at your facility as well. Corridors or rooms with poor lighting, wet floors, or uneven carpet increase the risk of a fall. Similarly, the proper adjustment and maintenance of medical furniture or devices like beds and wheelchairs is very important in helping to mitigate the risk of falls.

If a Resident Falls

Document everything you know about what happened. Talk to any team members or even other residents who witnessed the fall. Think about any changes that occurred in the last week, especially medication or environmental changes. Make sure your notes and records on the fall are consistent, including nursing documentation, IDT team notations, and the resident’s care plan, Kinder says.