Focus on Vision For Quality Of Life

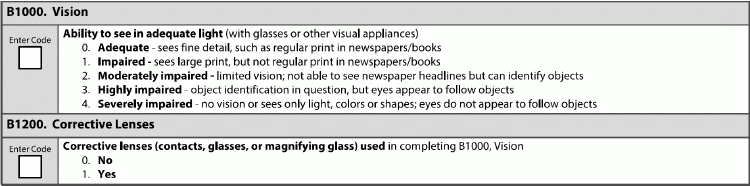

Don’t miss a key element of preserving quality of life. Vision is a sense most of us take for granted; we take its diminishment as we age for granted, as well. However, safeguarding vision — or taking the appropriate steps to correct it as it fails — can have an enormous effect on quality of life for residents, and make staff’s lives easier as well. Loss of vision can impact almost all aspects of a resident’s life, from everyday actions like reading the newspaper, to important life business like signing documents, to mobility and independence, as well as participation in social activities. Facility staff can help with vision issues in several ways, including ensuring that each resident has adequate lighting available; assisting with keeping track of any corrective devices; as well as the casual, day-to-day observations and formal assessments that can serve as a benchmark of maintenance or decline. Beware: Surveyors are looking out to make sure that facilities are helping residents maintain their vision by, among other things, looking for evidence that staff are helping keep track of any assistive devices. “Ensuring that residents have the proper adaptive devices (and are actually using them as care planned) appears throughout the Requirements of Participation (RoP) and Critical Element Pathways, so it’s important to ensure that residents receive appropriate treatment and providers assist them with obtaining any necessary devices to maintain their vision and hearing abilities,” says Linda Elizaitis, RN, RAC-CT, BS, CIC, president of CMS Compliance Group in Melville, New York. Assess Through Observation, Discussion, Testing The lookback period for the vision items on the MDS — B1000 (Vision) and B1200 (Corrective Lenses) — is seven days. The Resident Assessment Instrument (RAI) Manual has sort of unique instructions for assessing vision, encouraging the MDS coordinator to talk to direct care staff across all shifts for their observations of the resident and to talk to the resident directly, but also encouraging the MDS coordinator to “test” the resident’s vision. Vision loss may be a struggle that residents try to hide or to cope with on their own terms. The RAI Manual, on page B-10, suggests that MDS coordinators check the accuracy of staff observations and resident interviews by administering an informal vision test. 1) “Ensure that the resident’s customary visual appliance for close vision is in place (e.g., eyeglasses, magnifying glass). 2) “Ensure adequate lighting. 3) “Ask the resident to look at regular-size print in a book or newspaper. Then ask the resident to read aloud, starting with larger headlines and ending with the finest, smallest print. If the resident is unable to read a newspaper, provide material with larger print, such as a flyer or large textbook.” If residents are unable to speak or cannot read out loud due to a medical condition like aphasia or illiteracy, the RAI Manual suggests substituting numbers or pictures in the “appropriate” print size. If the resident does not speak English, you should have an interpreter, to help you ascertain that there aren’t any miscommunications or misunderstandings about a resident’s vision abilities. Code for Impairment Utilizing the resident’s regular vision device underscores the reality that you don’t need to administer a vision test to determine the resident’s vision in a quantitative way, as would a ophthalmologist; you’re simply ascertaining whether a resident can carry on in regular activities safely with the current equipment or situation. The RAI Manual’s guidance, on page B-10, instructs the MDS coordinator to choose value 0-4 for coding vision, with 0 being adequate (can see fine print) and 4 being severely impaired (sees only light, colors, or shapes; unable to follow objects as they move). If the resident has glasses but her vision does not appear to be adequate, the RAI Manual suggests spurring a reevaluation of the glasses prescription or assessing the resident for new or different causes of vision impairment. Similarly, if a resident has impaired vision but does not already use an assistive device, ask the resident about whether she has used corrective lenses in the past. Note: If a resident appears to have trouble identifying objects or tracking movement, it can be tricky to determine whether the issue is vision or perhaps symptom of dementia or even depression (if the resident is ignoring the test or refusing to participate). “As with any part of the observations of the resident, pay close attention when the resident is involved with other activities. Does the resident move her eyes when someone walks by or is there eye movement when a noise occurs in the room? Talk to other staff to determine what observations of object identification or eye tracking they may have noticed,” says Jane Belt Rn, MS, RAC-MT, RAC-CT, QCP, curriculum development specialist at the American Association for Nurse Assessment Coordination (AANAC) in Columbus, Ohio. Care Plan for Devices, Environment Care planning for vision includes supporting the resident with obtaining or maintaining assistive devices such as glasses, as well as helping coordinate appropriate appointments and transportation to and from those appointments. You may find situations where a resident’s reality does not fit neatly into the “adequate to severely impaired” spectrum that the RAI Manual offers; for example, if a resident is blind in one eye but makes out OK with the other, functioning eye. In these situations, care planning is especially important because the MDS isn’t specific enough to encompass fully the resident’s situation. If a resident uses glasses or another assistive vision device, make sure the care and maintenance of that device is part of that resident’s care plan. In terms of compliance, surveyors are not looking for facilities to provide the residents with the actual devices, only to help them with their availability and use. “While the regulation (F685) does not require facilities to provide the devices or conduct related evaluations, providers are tasked with assisting the resident/representative with locating and using available resources. This includes situations where the resident has lost his/her assistive device,” Elizaitis says. “Take a peek at the Activities of Daily Living and Communication-Sensory Critical Element Pathways to assess your facility’s vulnerabilities,” Elizaitis says. Don’t neglect the physical environment of your facility, either. Knowing about and addressing any environmental viabilities, like a dim hallway or bathroom, can make a huge difference in residents’ safety. Resource: Find out more about the significance of adequate lighting (and how providing proper lighting can help to alleviate safety concerns and resident dependence) in this resource provided on Pioneer Network’s website: www.pioneernetwork.net/wp-content/uploads/2016/10/Lighting-A-Partner-in-Quality-Care-Environments-Symposium-Paper.pdf.