Avoid these common mistakes when coding Signs and Symptoms of Delirium.

The Confusion Assessment Method© (CAM©) was new to the MDS 3.0 and was not included on the 2.0 version, and many staff are still getting used to utilizing it properly. But the CAM© is an important MDS assessment tool, and you can avoid making mistakes in commonly confusing areas of the assessment by heeding expert advice.

Background: “The CAM© is a tool that was originally developed for use in the intensive care unit and it’s been used in many other settings since then, and has been adapted for use here on the MDS 3.0,” explained Karen Schoeneman, owner of Karen Schoeneman Consulting and recently retired technical director for the CMS Division of Nursing Homes, in a recent Centers for Medicare & Medicaid Services (CMS) instructional session. The CAM© essentially helps you to figure out “whether there’s fluctuation in mental status or if there’s an acute onset of a mental status change.”

Find the Resident’s Baseline

Understand: “The biggest thing is you need to really know what is your baseline for the resident?” Schoeneman stated. This is obviously easier if you know the resident, but what if this is a new admission?

First, you can look back at the resident behavior during the Brief Interview for Mental Status (BIMS) or the Staff Assessment for Mental Status to determine a baseline. You should also review the medical record during the seven-day look-back period.

But with a new resident who has little history at your facility, you’ll likely need to spend more time interviewing the family members to get a sense of what the resident was like prior to admission, Schoeneman said. “We couldn’t have that knowledge until we’ve taken care of that resident for a period of time.”

Also keep in mind that you’re looking for behavior that may fluctuate over short or longer intervals. “So, you may see that a symptom — an indicator for potential for delirium — may happen within a five-minute period of time where it fluctuates very quickly, or it may be that it fluctuates between morning and evening or between Monday and Friday,” Schoeneman explained. But you must keep this fluctuation within the look-back time period.

Avoid Mixing Up Delirium with Dementia

If there’s a rapid decline in cognition, consider delirium instead of dementia, according to a Dementia Care 2013 conference presentation by Tim Gieseke, MD, CMD, associate clinical professor at the University of California San Francisco and a multi-facility medical director. At the same time, dementia is the strongest risk factor for developing delirium, with 25 to 75 percent of delirium patients having co-morbid dementia.

Also, Gieseke cautioned to beware of certain medications that can challenge cognition, such as:

Look to Your Interviews for C1300A — Inattention

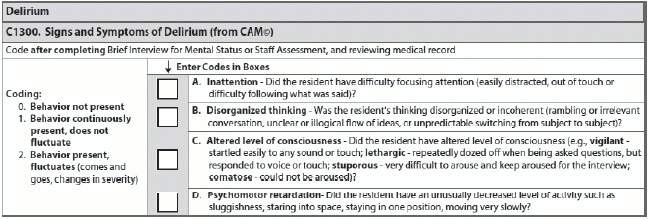

You have four items to evaluate in the Signs and Symptoms of Delirium section: inattention; disorganized thinking; altered level of consciousness; and psychomotor retardation. For each item, you must determine and code one of three responses: behavior not present (0); behavior continuously present, does not fluctuate (1); or behavior present, fluctuates (2).

Look here: “Evidence of inattention may be found during the interviews,” Schoeneman noted. “So think about your interviews. If you just completed some of your interviews and you had to constantly bring that person back to you to have [him] pay attention when you were doing it, what is that informing you? That [he] had inattention.”

But you would code “2” for “behavior present, fluctuates” if the “resident’s attention varies or sources disagree in assessing sources of attention,” Schoeneman instructed. “Day staff is saying one thing, evening staff is saying another, and what you’re showing is that the resident is a little different — [he’s] fluctuating from how [he is] in the morning to how maybe [he is] in the evening.”

Tread Carefully When Evaluating C1300B — Disorganized Thinking

“Disorganized thinking is evidenced by rambling, irrelevant or incoherent speech,” Schoeneman said. “It’s unclear or illogical flow of ideas. It’s unpredictable switching from subject to subject.”

Snag: Where many staff trip up in this area is when the resident has problems with orientation to reality. But remember that you’re not testing that — for disorganized thinking, you’re testing the resident’s thought process.

Example: “The resident responded that the year is 1837 when asked to give the date, and the medical record and staff indicate that the resident is never oriented in time but has coherent conversations with the staff,” Schoeneman posed. “For example, the staff reports the resident often discusses his passion for baseball.” Although it might seem wrong, in this case you would code “0 — behavior not present” for disorganized thinking.

You would code “0” if this resident can have a conversation with you about baseball and sticks to that theme of baseball all the way through the conversation, Schoeneman said. However, you would maybe code “1 — behavior continuously present, does not fluctuate” if you start the conversation on baseball, and then the resident jumped around to basketball, then talked about golf, and then talked about lunch, with no clear relationship between the subjects.

Altered Level of Consciousness: Don’t Get Hung Up on ‘Comatose’

For C1300C (Altered Level of Consciousness) you have four factors to consider, most of which are pretty straightforward:

Misconception: “People get hung up on ‘comatose,’” Schoeneman pointed out. “This is not the diagnosis comatose as in one of the first questions that we answered in the MDS. So this is not the persistent vegetative state or anything like that.”

“This may be someone who’s having maybe an acute mental status change or … has some sort of medical condition where they’re unresponsive to us,” explained Schoeneman. A diagnosis of comatose does not have to be present for you to note this behavior in C1300C.